(Or all I know about leadership I learned in Culinary School)

“Yes, Chef!” was the first thing I learned on my first day in Culinary School. The response was hard at first, then turned into a habit. Now, it’s just part of my lexicon. The Chef Instructor explained that you didn’t do it because the Chef has a big ego or needs to be shown respect. The response was required to ensure that in a busy and loud kitchen during a dinner service, a request was heard. A simple yet very necessary practice. It reminded me of Japanese management culture where a nod from a colleague didn’t necessarily mean they agreed with you – it meant they heard you. This was the first of many lessons in management and leadership that came from my culinary education.

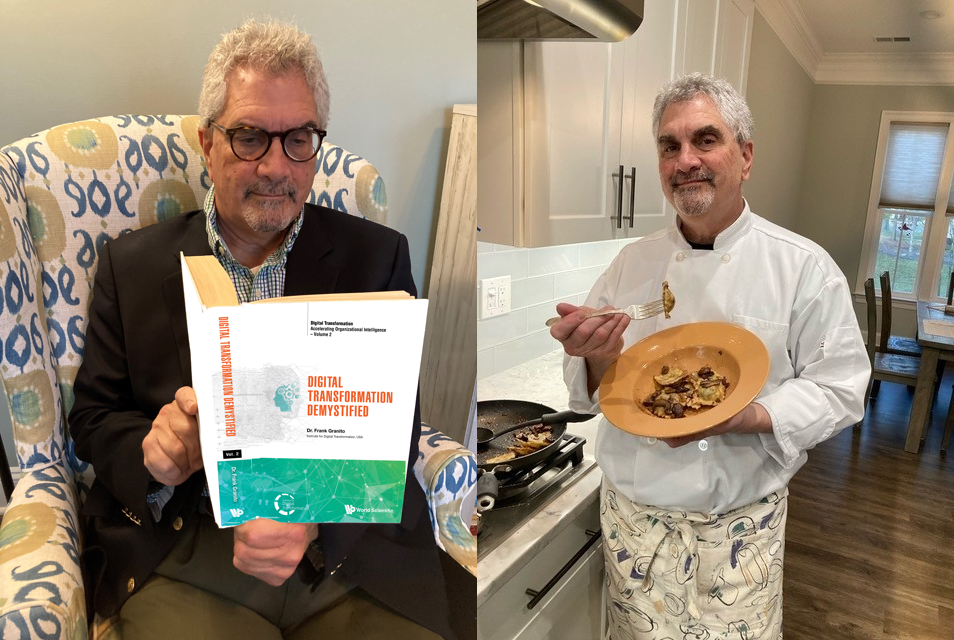

Growing up in an Italian home, the kitchen was the focus of life and activity. It was the very garden where the Mediterranean culture, lifestyle, and food was sewn and harvested. As a result, almost everyone in my family is a very good home cook. It was from my mom and grandmother, neither of whom were professionally trained, that I learned the joy of using food to serve family and friends. My introduction to good customer service! So, in 1978, about the time I was preparing to enter my senior year in college, I informed my parents of my desire to go to culinary school. “Hai una capa fresca,”. Literally translated to “you have a fresh head,” but idiomatically meaning “you have crazy ideas.” As a result, I completed college, got a job, built a career in Information Technology, and earned both a master’s degree and a doctorate. During my 45 years as an IT professional, I did almost everything one could do in the field including leading major transformation efforts, all while scratching my culinary itch by honing my cooking skills in my home kitchen. Then, I “retired.” Well, not really. But I have slowed down and found that I had time that needed to be filled. There are only so many rounds of golf to play and places to travel. There needs to be continual learning and personal enrichment. When most people stop their education, that’s when I decided to start…again. To my surprise, I learned much more than just culinary skills.

I learned that a Chef is a mentor, a technician, an artist, a customer relationship manager, an expert in time management, a developer, and sometimes by necessity, a dictator, among many other qualities required of a leader. How does one get that way? What is it about being a Chef that we can all learn to be a better leader? What habits and skills are learned and then required? As I came to find out, the similarities between a Chef and any other organizational “leader” are obvious and they are built from the habits learned in the professional kitchen. What could these possibly be, you may ask? Let’s look at a few.

- Mise en place – This is a French term for having all your ingredients measured, cut, peeled, sliced, grated, etc. before you start cooking. Pans are prepared. Mixing bowls, tools and equipment set out. It is a technique chefs use to assemble meals so quickly and effortlessly. This was drilled into us as culinary students and a good part of your grade depended on it. You couldn’t start your procedures unless you were “ready.” At the Institute, we stress Readiness for Transformation. Like an army or a sports team, or a Chef, you don’t roll into battle, just take the field, or start your recipe without having everything lined up ready to go. Why would you undertake a disruptive operation like an organizational transformation without being ready?

- Running a line – This is the heart of service. When one orders a meal, a message gets sent to the kitchen to “fire” (start) the dish. However, there are usually at least 2 orders per table. Each order may require a different station on the line. Salmon may require a grill station. Shrimp may require a sauté station. Both may require a fry station for a side dish as well as a Garde manger station for side salad. All these “silos” need to be managed to come together. At the same time. Under pressure. Each silo may be excellent, but how they come together is what matters. Organizational “silos of excellence” would not be tolerated by neither the Chef nor the customer. Why should your organization tolerate that? Would your customer tolerate that?

- Order of Production – This involves more than just following a recipe, which is a repeatable and sustainable process, but in this involves multiple recipes for production for every component of your dish. Thus, a Chef must look at not only proper processes, but also “layered” processes. Potatoes could take about an hour while shrimp could take as little as three minutes. A chef makes sure the components of the plate come together at the same time. Sequencing work and multi-tasking is an important part of the Chef’s responsibilities. This is Project Management at its core.

- Leading a brigade – This is the essence of using your resources effectively and efficiently by assigning and overseeing work. This is no different from any other leadership responsibility managing resources.

- Expediting – This responsibility is the last stop before a dish goes out to a table. An expeditor, or running “expo,” is making sure the plate is complete as designed and ordered. It is also making sure the plate is clean and the food looks good. If it is not, it goes back to the line for correction or in more drastic cases, to be made again. The Chef running the line is doing quality control along the way. The expo is doing quality assurance – was this done correctly? As a customer, if you’ve ever sent a dish back to the kitchen because it wasn’t correct, then you know how annoying that can be. Why should you allow this to happen to your customers. Would you tolerate this? There is keen attention to detail and customer focus. A customer should expect excellence and consistency.

Finally, in my head I hear shouts of “heard,” “corner,” “behind you,” and “sharp.” These are the sounds of a team working together, thinking about each other, and the products they are producing for a customer. “How long on that risotto,” calls the Chef. “Two minutes, Chef,” responds the sauté cook. Can your team give you an accurate estimate of task completion? This is the language and culture of the kitchen, much like there is a language and culture of your organization. This is the culture and language taught in culinary school and then on the job as a professional cook and then Chef. These are the habits one learns, one practices, and the ones a good Chef demands of their team. Shouldn’t you be teaching your teams the culture, language, and habits that you want in your organization?

Despite my “fresh head,” I completed my Culinary Degree at age 65 and got more than just great cooking knowledge and skills. I learned about leadership as well. Does this make you want to go to culinary school? It should. Not only might you learn good leadership skills, but you’ll also learn how to be a gourmet cook! Perhaps if you practiced leadership like a Chef practices leadership, your organization might earn a Michelin Star.

I wonder how many of the great Digital Transformation Leaders are also Chefs.

Tag/s:Business TransformationEducationOrganizational ChangePersonal Development

How do we crack the code of such brilliant synchronicity when the various cooks in the kitchen (sorry!) are in different offices, possibly even different time zones? They are still part of a single team, but don’t act that way and perhaps the last thing they would want is to be in a kitchen together. (I wonder what sort of dish they are serving up?)

Cherri,

Thanks for the comment. In fact, this is quite common. On a small scale, think of a banquet: you’ll have appetizers, mains, and desserts. These could be serviced by different teams. On a larger scale, you might have an Executive chef in charge of a facility that has several restaurants (such as a casino or a resort) each with a Chef di Cuisine or Lead Sous Chef that have to be run AND may share products and team members. Then you might have a corporate chef who has a team supplying products to different properties. Each of these properties have there own lead chef and staff executing a menu. These menus usually share common products and also have local menu items distinct to that location. This is most common in the dessert/pastry application where not every property has the luxury of its own pastry chef.

If you don’t want to be in the kitchen together, there’s always another property you can go to. Or simply get another job.

In these examples, it is no different from any other organization and the uniqueness of their culture.

I hope I addressed your question.

Chef Frank